This time I check out a ‘Ramen Event’ at Le Duc

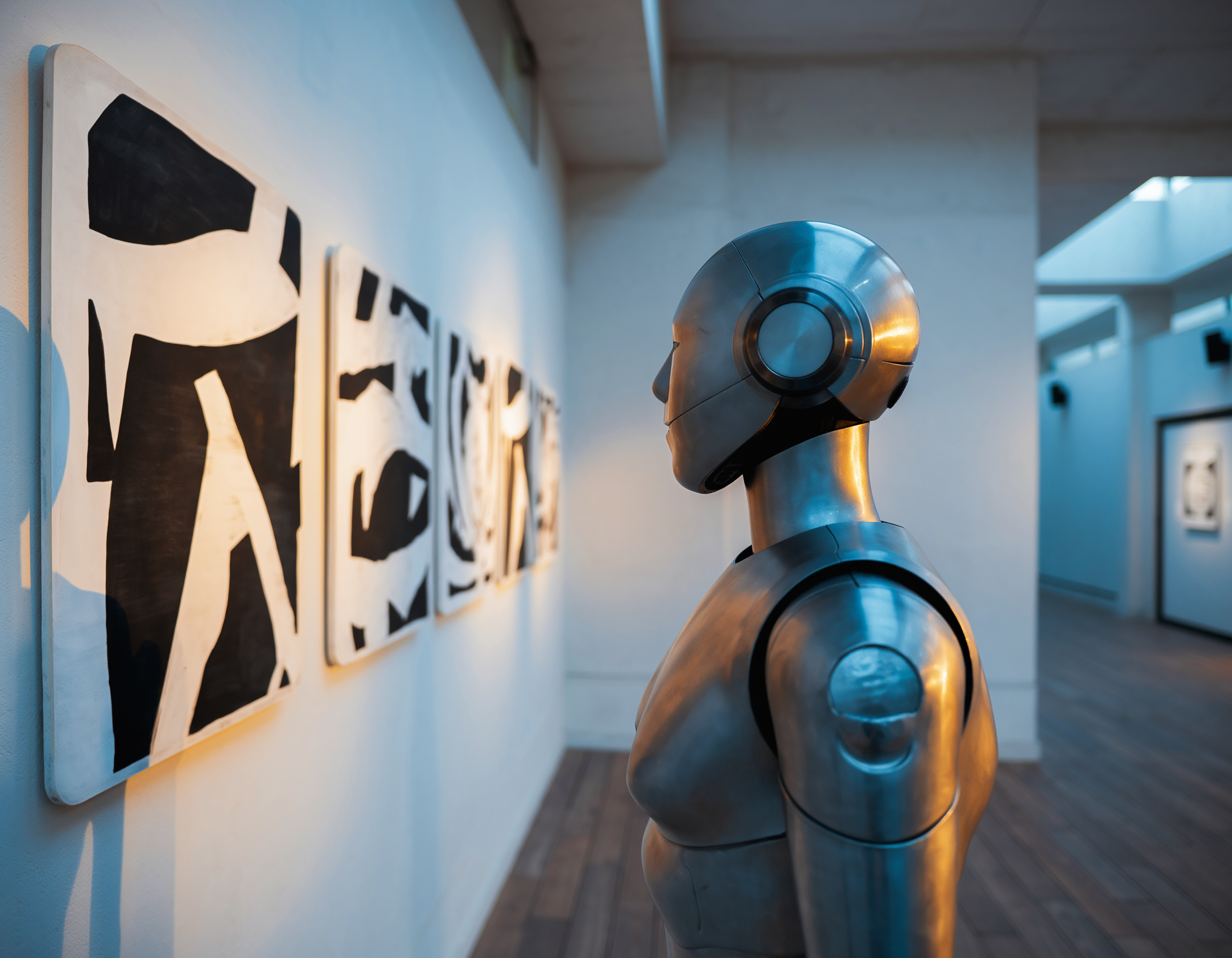

Read moreVideo Games, AI, and Modernism

AI image generated by Adobe Firefly

Some speculations on why early video games were met with enthusiasm, despite their rudimentary graphics. This contrasts with AI generated content that need to get very good before it took off.

Read moreReview of Grotto Efra

My thoughts on a visit to a Grotto in the Italian speaking region of Switzerland.

Read moreReview of Mine Berlin

Mine review - a respite from a hot summer day.

Read moreTwin Peaks retrospective

My retrospective review of Twin Peaks. With viewing order…

Read moreReview of Funky Fisch

Review of Funky Fisch restaurant in Berlin, Germany.

Read moreWhy I use Creative Commons

Discussion on why I use Creative Commons licensing for my blog post.

Read moreSome thoughts on Cartoonist Kayfabe

My reflections on the Cartoonist Kayfabe channel, following the sad news of Ed Piskor’s passing.

Read moreReview of Shiori

Review of the Shiori restaurant in Berlin, Febuary 2024

Read moreReview of AV Restaurant

Review of AV Restaurant in Berlin. Visited in December 2023

Read more